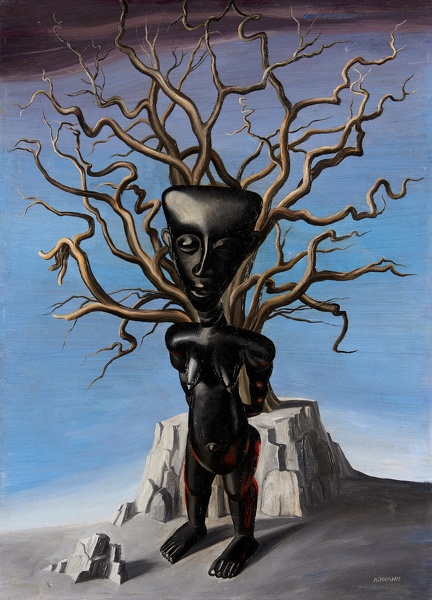

Medusa Grown Old, 1947

Framed (ref: 9885)

Oil on panel

21 ½ x 15 ½ in. (55 x 39.5 cm)

Tags: Marion Adnams oil panel allegory 49 pictures Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900 - 1950 Rediscovering Women Artist RELIGION Works for Paris

Oil on panel

21 ½ x 15 ½ in. (55 x 39.5 cm)

Tags: Marion Adnams oil panel allegory 49 pictures Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900 - 1950 Rediscovering Women Artist RELIGION Works for Paris

Provenance: With the artist until 1971; Private Collection

Exhibited: Cathedral Church All Saints Derby, An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Marion Adnams, 27th October-5th November, no 75

In 1947, Marion Adnams – the leading Surrealist in Derby – borrowed a small African sculpture from the city’s museum for closer study.

'One day I made a drawing of her, and, when it was finished, dropped it down on the floor by my chair. By chance, it landed on a drawing I had done the day before – a drawing of an ancient English oak tree, with gnarled, twisting branches. They framed the head of the African figure, and there she was – Medusa, with snakes for hair.'

Those snakes are the Gorgon’s most luridly distinctive attribute. But Adnams gave her new composite work a more unexpected title, Medusa Grown Old.

In classical myth, Medusa died young. A mortal, unlike her sister- Gorgons, she was beheaded by the youthful hero Perseus, heavily briefed by gods and fates. At her death, Medusa was heavily pregnant by the greatest sea god, Poseidon; sources differ as to her consent. The winged steed Pegasus sprang from his slain mother’s blood, and from Pegasus’ hoof-beat came in turn the Hippocrene spring – vital source of all artistic inspiration.

Set apart from any such cyclical destiny, Adnams’ African Gorgon presides over barren rock and blasted bough, the stricken world of Modernism and its post-war legacy. Adnams kept the sculpture – long after the picture was finished –, but then returned “Medusa” after an attack of nocturnal panic. “After that I confined myself to shells and butterflies – very beautiful and much safer.”

Commentary by Minoo Dinshaw, author of Outlandish Knight: The Byzantine Life of Steven Runciman (2016). He is currently investigating the workings of the god Mercury in seventeenth century England.