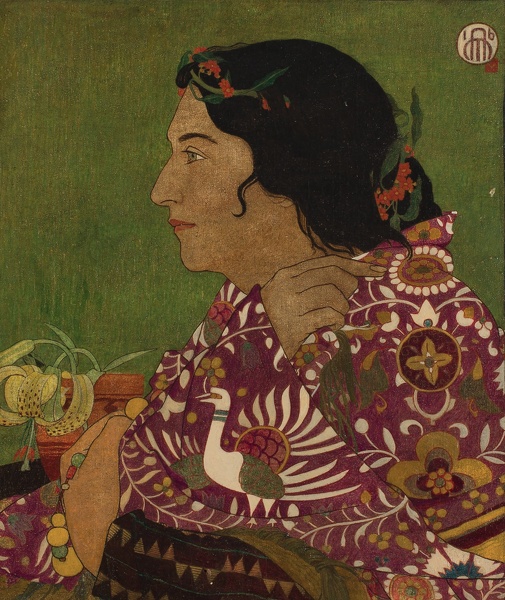

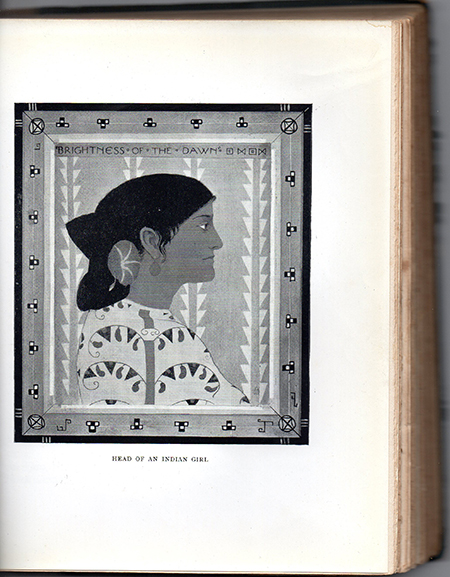

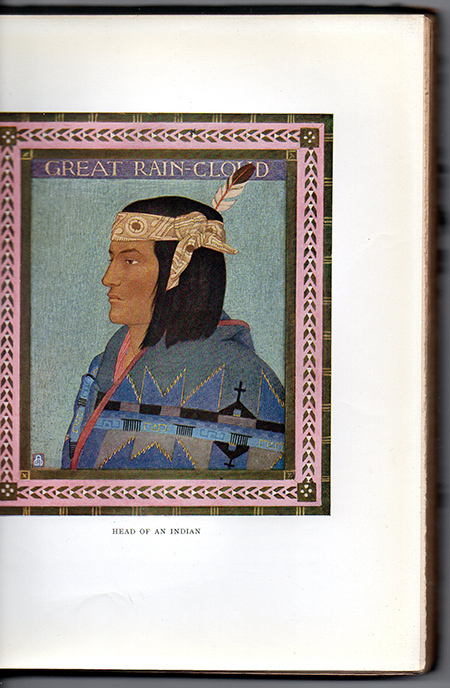

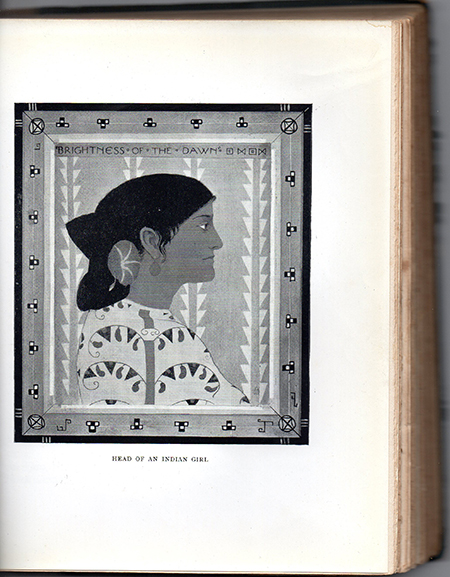

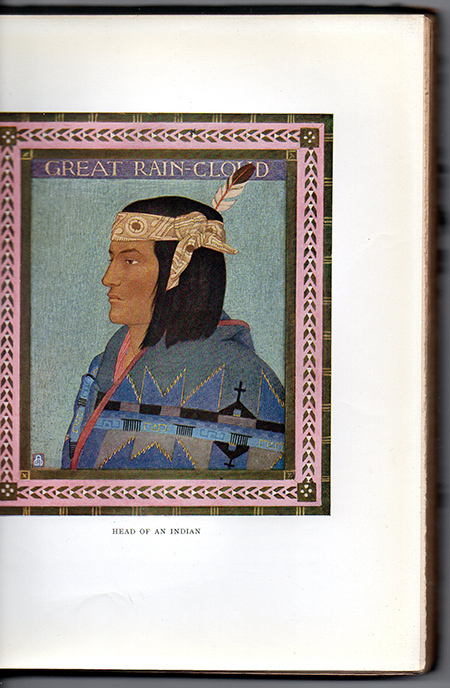

During his time in California Maxwell Armfield was particularly struck by the ingenuity of the patterning of the native woven blankets, and made a series of oil studies - mostly in profile - of local figures wearing them. Two of these are reproduced in his book 'An Artist in America' (Methuen, 1925) in which he wrote: 'The Navaho, who originally stole the Hopi flocks, have made good use of their theft, and now weave as well, if not better than their masters, the blankets which are such blazing comments on the wild natural phenomena amongst which they live.

Maxwell Armfield (1881-1972) Quaker and artist, and his wife, Constance Smedley, play write and author, left England for the USA during the First World War due to their pacifist convictions. Armfield had trained in Birmingham and Paris and was associated with the group of Birmingham tempera painters and craftsmen - Joseph Southall, Arthur & Georgie Gaskin, Henry Payne, et al. - exhibiting with them at The Fine Art Society in 1907. As a committed Quaker his pacifism attracted considerable abuse and in 1915 he and his wife left the UK for America, where they were to spend seven years, living in New York, Chicago, Santa Fe New Mexico, San Francisco and La Jolla. For two or three seasons, in company with the actress Ruth St Denis, they ran the Summer School of Theatre at Berkeley. During these years Armfield contributed articles to the Christian Science Monitor describing his interest in both the landscape and the indiginous people; a number of these articles were later published in book form as An Artist in America (Methuen & Co. 1925). The following extracts (taken from pages 27-29) give a sense both of his interest as an amateur anthropologist, interested in their crafts and customs, as well as an artist, while the two illustrations he included (attached) demonstrate that he consciously set out to make a comparative sequence of studies of racial types and their woven crafts, though, in each case he limited himself to the word 'Indian' thus avoiding the pitfalls for a foreigner of making tribal distinctions. In the chapter (pp. 27-37) headed 'Indians'- no other chapter heading was put in inverted commas - he wrote that, 'When the train draws up at Bakersfield or Albuquerque, the platform will be dotted by those people: so uncouth in the midst of the machinery, so unlike the Indians of Hiawatha and the Wild West shows. 'He went on to say that 'The American aborigines are not Indians, of course, and even the improved form of 'Amerindi' which locates them, however conveniently, is equally incorrect. They are of many nations, speaking different languages, living different lives and with different arts. As one approaches the Pacific, and therefore the Orient, he begins to feel that these strange people - more yellow than red - have more in common with China than India.[...] 'Of the tribes one most sees in a radius not too far from the railway, the Hopi and the Navajo are the most distinctive... Here one sees few feather head-dresses, and no wampum or wigwams. On the other hand, the arts and crafts are much more in evidence and have reached a much more advanced stage.... 'The La Plata district of South West Colorado was once populated by a race far in advance of existing tribes of Amerind people from the cultural standpoint... The Hopi Indians are probably the descendants of these people, who were driven out of their homes by warlike tribes from the north... [but] like so many other defeated peoples, they have proved the copy book maxim about the pen and the sword. 'They have, however, influenced their various enemies for good and have given them blessing for cursing in a number of directions. The Navaho, who originally stole the Hopi flocks, have made good use of their theft, and now weave as well, if not better than their masters, the blankets which are such blazing comments on the wild natural phenomena amongst which they live. 'They share with the Hopis a passion for scarlet, though they do not, like the milder people, bind it about their long blue-black hair nor so freely use it to envelope themselves. To the Amerind, colour is intensely symbolic and sacred; quite definite in its meaning. Scarlet implies all that they associate with the beneficient light and warmth and fertilizing qualities of the sun. They seem to feel about the colour what Blake meant when he called it the bringer of life into memory.

We are grateful to Peyton Skipwith for his assistance.